CMA EXPLAINS

As health ministers across the country grapple with intractable wait lists for everything from primary care to specialized surgeries, some are turning to the private sector for help. Although privatization brings American-style health care to mind for many Canadians, there are other models — each with pros and cons.

The Canadian Medical Association (CMA) believes now is a critical moment to speak up for the health system we want, grounded in a shared understanding of the one we have and with a focus on access, equity, quality and system capacity. Here are some basics to start with.

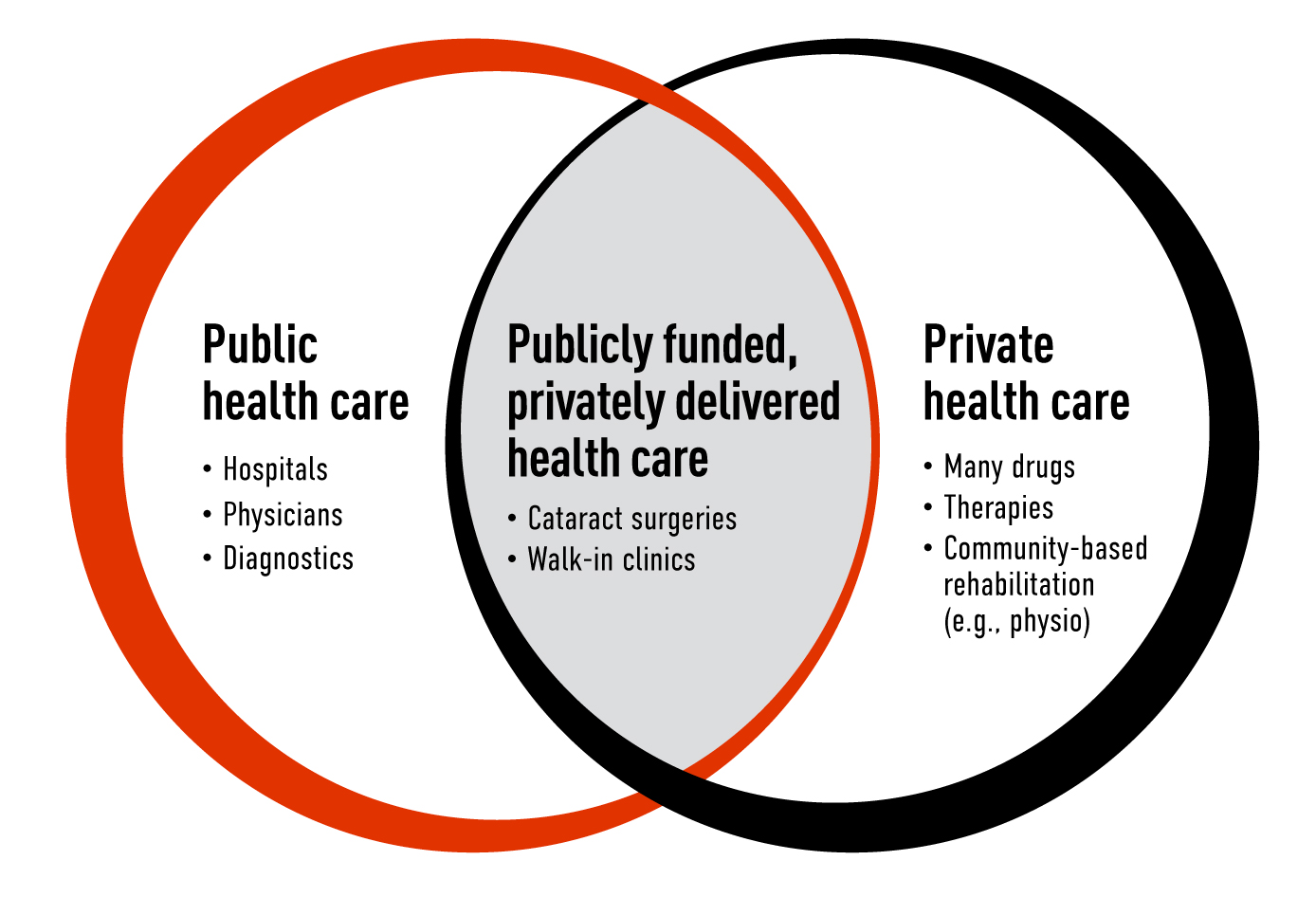

What’s covered by “public” health care

In the 2023 federal budget, Ottawa committed $196.1 billion in health funding over 10 years. To receive their portion, provincial and territorial governments must follow established criteria for public health insurance — what most of us refer to simply as public health care.

Not all aspects of care are covered. The focus of Canada’s public system is on hospitals, diagnostics and physicians. That’s why, for example, a broken ankle will be X-rayed and fixed at no direct cost to you, but the out-patient physiotherapy required to rebuild its strength may not.

And while public health care must be overseen by provinces and territories, they can choose private facilities or providers to deliver care, as long as patients aren’t charged for services covered by those health cards in our wallets.

Examples include:

Whatever services are covered, and however they’re delivered, the interconnectedness of health care means any change can have a domino effect — for better and for worse.

The patient with the broken ankle, for instance, might benefit most from post-surgical physiotherapy. And for someone with private insurance or the personal funds to pay out-of-pocket, a private provider might offer the fastest, most effective care.

For someone who can’t afford private services, on the other hand, further care from a publicly funded physician or hospital may be the only option, impacting not only their own health outcome or wait times but those of other patients as well.

“The conversation is not an easy one, but the time is now for an open and honest dialogue on the way forward out of this health care crisis. Services must be there for Canadians when they need them, and solutions must be grounded in the lived experience of those seeking and those providing care.”

Dr. Kathleen Ross, CMA president

Standards for health care, everywhere

There are five criteria for public health insurance set out in The Canada Health Act:

- It must be universal, provided to all residents of a province or territory.

- It must be comprehensive, covering all medically necessary services provided by hospitals, physicians and dentists (when their services must be performed in a hospital).

- It must be accessible to any resident with medical needs – unimpeded by discrimination of any kind, including the ability to pay for services.

- It must be portable, ensuring care for residents who are travelling within Canada or who move from one province or territory to another.

- It must be publicly administered, operated as a non-profit by a government or authority accountable to it.

The impact of public and private care on Indigenous Peoples, who continue to experience extreme barriers to comprehensive, equitable health services , deserves particularly careful consideration.

The balance of public and private care we have now

The private sector’s role in health care can be obvious — when you get a bill from the dentist or optometrist, say — but not always. Patients are not charged for medically necessary services at privately owned walk-in clinics, for example, because these services are publicly funded by the government. The same is true for blood tests and ultrasounds at privately owned labs and clinics.

To get a sense of the current ratio of private to public care in Canada, here’s a snapshot of how things break down in the country’s largest province, Ontario, which also has the highest concentration of health providers.

![]()

PUBLIC: Physicians

Physicians working outside of hospitals operate as small businesses – covering their own overhead and clinical expenses – but 98% of their services are covered by public health insurance.

![]()

PUBLIC: Hospitals

Hospitals are independent corporations, largely non-profits funded by the government. Basic hospital care is covered by provincial health insurance. Extras such as private rooms are not.

![]()

PRIVATE: Medicines

Medicines provided in hospital are publicly funded. So are some drugs for select groups of patients. Everything else is paid for out-of-pocket or by private health insurance.

![]()

PRIVATE: Counselling

Other than counselling provided by a physician and some mental health and addiction programs, counselling services (for example, by a community-based psychologist) are paid for by private insurance or out-of-pocket.

![]()

PRIVATE: Dental

Patients are charged directly. (Although the new Canada Dental Benefit will cover care for some patients based on income.)

![]()

PUBLIC: Tests and diagnostics

There are exceptions, but most lab tests and diagnostic scans in Ontario are publicly funded and privately delivered.

![]()

PUBLIC/PRIVATE: Long-term care

More than 43% of long-term care facilities are public or publicly funded non-profits, with the rest operated by for-profit businesses. Accommodation fees are geared to income.

![]()

PUBLIC/PRIVATE: Home care

A provincial agency decides who’s eligible for public coverage and for how long. Those who don’t qualify can either seek community services, which may require co-payments, or private help.

![]()

PUBLIC/PRIVATE: Virtual care

Virtual care is evolving — fast. The province’s 24/7 phone line and appointments scheduled by providers are covered. Patients seeking private care directly, including text, phone and video consultations, are not.

The postal code effect

Where you live affects the balance of public and private care.

Patients’ options for Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) scans are a good example. All medically necessary scans must be covered by provincial and territorial health insurance. The catch is how fast you’ll get one.

Machines cost about $3 million. In remote regions like Nunavut and the Northwest Territories there are none; if you need a scan, you’ll need to travel. Elsewhere, there are machines — but average wait-times range from 33 to 91 days.

Some governments — for example in British Columbia and Ontario — have addressed this problem by funding private companies to conduct MRI scans, with services covered by public health insurance at no cost to patients.

Saskatchewan made private-pay MRIs accessible in 2016, but clinics must match every privately funded MRI with a spot for someone else on the public waiting list.

Other provinces have opened access to diagnostics that are both privately funded and privately delivered: Alberta established the first private-pay clinic in Calgary in 1993. Now, they also exist in British Columbia, Quebec, New Brunswick and Nova Scotia.

Even where private-pay scans are not available, as in Ontario, Manitoba, Prince Edward Island, and Newfoundland and Labrador, patients can go to neighbouring jurisdictions.

Paying the bill for private care

A large proportion of privately funded health care is covered by insurance companies.

72:28

As of 2022, governments paid for 72% of all health care. The rest was paid by patients out-of-pocket (11%), through private health insurance (15%) or other sources (2%).

27 million

About 27 million Canadians have private insurance. Approximately 66% have plans attached to employers, with the rest paying for their own insurance policies.

$1,000

On average, Canadians spent more than $1,000 out-of-pocket on health care in 2020.

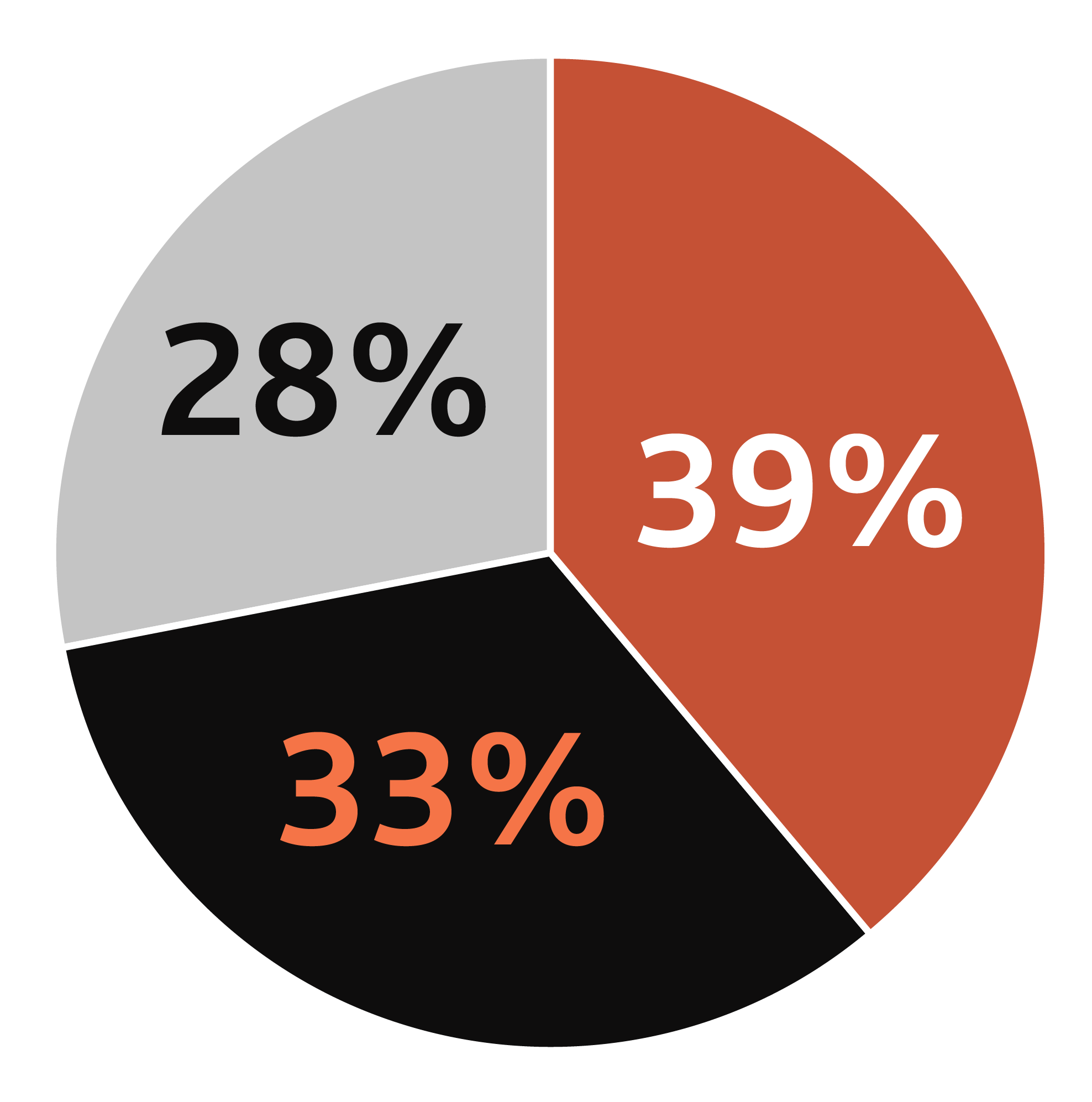

What Canadians think

Prior to the announcement of the 2023 federal budget, the Angus Reid Institute surveyed Canadians on the possibility of increased private funding and delivery of care. Here’s how respondents were divided in their thinking:

Private care proponents

Think privatization is a necessary evolution of care.

Curious but hesitant

Acknowledge benefits to both public and private care.

Public health proponents

See little to no place for privatization.

“We need to be clear on the realities of our system. There is so much misinformation out there. Many people aren’t aware of the current public-private mix of health care services. We can only stand for equity and timely access for all if we’re working with a common awareness of the full scope of options available.”

Sudi Barre, CMA Patient Voice

Overall, when asked whether patients should be allowed to pay out-of-pocket for faster access to diagnostic tests or select surgeries, 43% of respondents said they supported the idea and 47% opposed it.

SOURCE: Survey conducted with randomized sample of 2,005 Canadians on Feb. 1-4, 2023, by the Angus Reid Institute. Margin of error +/- 2%, 19 times out of 20.

Where the CMA stands

The CMA’s current policy on public and private care is based on guiding principles including:

- Timely access: Canadians should have timely access to medically necessary care and individual recourse when wait times are unreasonably long.

- Equity: Access to medically necessary care must be based on need and not on ability to pay.

- Accountability: Public and private health providers should meet the same standards for patient outcomes, full-cost accounting and value for money.

Our principles haven’t changed, but pressure on the health system has — which affects patients’ access to quality and timely care and providers’ well-being.

That’s why we’re launching cross-country consultations with both the public and the medical profession. What we hear will inform our policy moving forward, and our recommendations for action at a national level.