Highlights

- Canada has no coherent national approach for collecting and sharing crucial health data.

- We don’t have enough information on which resources are needed where, or even who is best positioned to provide care.

- This contributes to health inequities, rising costs, workforce pressures and poor accountability for health outcomes.

CMA EXPLAINS

According to a 2021 Commonwealth Fund survey, Canada’s health system ranks 10th out of 11 high-income countries, ahead of only the United States. There are many ways to change this. But choosing the best solutions depends on a clear understanding of the gaps in the system.

Right now, Canada has no coherent national approach for collecting and sharing crucial health data. We don’t have enough information on which resources are needed where, or even who is best positioned to provide care. Both health professionals and patients also suffer from the lack of interoperability between electronic health records. This contributes to health inequities, rising costs, workforce pressures and poor accountability for health outcomes.

The Canadian Medical Association (CMA) has been calling for urgent action to improve health data — to modernize care, inform better workforce planning and allow for more transparent performance tracking.

“We can’t improve our health care system without collecting and sharing data. The more data we possess, the more we can accurately track our progress and ensure transparency.”

— CMA President Dr. Kathleen Ross

What we don’t know about health care

Organizations such as the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) provide essential data. But there are many unanswered questions — and across Canada’s many health authorities, there is no national data set.

Here is a small sampling of what we don’t know:

Where are physicians and other health care workers needed most? What specializations are needed and where?

While individual health authorities have information about staffing shortages and wait times, we don’t have a bird’s eye view to understand where resources would be best allocated.

Are there overlapping scopes of practice between health care practitioners?

The most effective use of the health workers we have is difficult without information on what they’re uniquely skilled to do — and how they might provide higher-impact care as part of a team. For example, in 2023, Ontario pharmacy professionals were permitted to prescribe medications for 13 minor ailments — such as for dermatitis and uncomplicated urinary tract infections — reducing the need to visit a family doctor for these minor issues.

How many internationally trained physicians arrive in Canada every year ready to practise?

There’s no national data to answer this question. The federal government recently announced funding for the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada to help eligible candidates apply for work within three to four months of arrival, as opposed to the current wait time of six to 24 months, and funding to the Medical Council of Canada to expand Practice-Ready Assessments. But there is no systematic data collection on the entry of these physicians to practice.

How many physicians exit the profession every year?

The indicators available to know when doctors exit the profession include giving up a medical license, ceasing billing under provincial insurance or ceasing payment of professional dues. But there’s no national count of how many physicians retire every year.

Is there any comprehensive data available about equity, diversity and inclusion within medicine?

Beyond gender, no.

How health data can help — and save lives

Integrated health human resources planning

Current health workforce planning is siloed and does not account for changing professional lifespans, demographics or population health needs. The first step toward the right kind of care, in the right places, at the right times, is transparent and shareable data on health care labour across professions and jurisdictions, including projected retirements, rates of attrition and training.

Population health management

Data helps health leaders understand patient needs now and in the future so they can allocate resources both to prevent illnesses before they start and support the best care when it’s needed. This includes examining social determinants of health, such as housing, food security and economic stability, as well as Canada’s aging population and communities at risk for particular conditions.

Empowering patients and providers

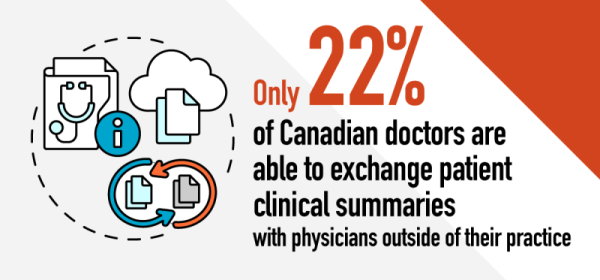

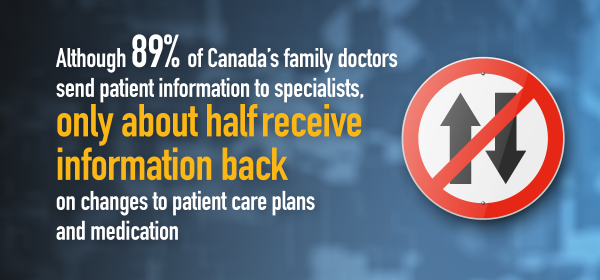

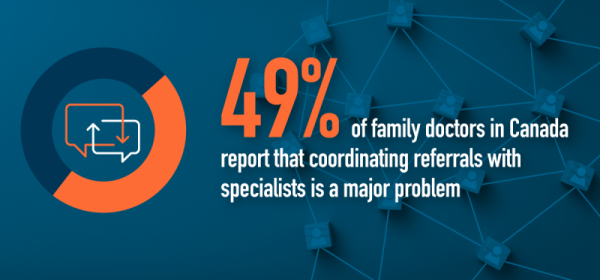

Access to personal health information — immunization records or lab results — makes it easier for patients to manage their own care and helps build a more patient-partnered system. For providers, being able to share information across health professions and jurisdictions is invaluable; it cuts down on unnecessary tests and offers a more holistic view of patients.

COMPREHENSIVE CARE

A lack of interoperability makes exchanging health data between physicians difficult.

Sources: Canadian results of the 2022 Commonwealth Fund International Health Policy Survey of Primary Care Physicians, Improving Accountability in Health Care for Canadians (CMA)

What's next

Calls for improved health data are making a difference.

Dr. Alika Lafontaine, the CMA’s 2022–23 president, is part of an interim steering committee for Health Workforce Canada, a new organization established, among other things, to improve data collection.

It’s part of recent federal efforts to address the dearth of health data. In 2023, the federal government announced $505 million in funding over five years to CIHI, Canada Health Infoway and federal data partners. This funding will include the creation of a Centre of Excellence on health worker data and planning, and aims to improve the access and use of data in health care.

As part of a $46.2-billion increase in federal health funding over the next decade, provinces and territories must also commit to new ways of collecting, using and sharing data.

With these landmark funding deals, accountability is essential. A recent CMA report provides benchmarks to measure how the health system is performing and what needs to be improved — including how patients and doctors access and share data.

What physicians can do to help

Collaboration with physicians and learners of all ages, stages and specialties, from rural and remote communities as well as big cities, is essential for a better way forward.